The Prehistoric Archaeology Blog is concerned with news reports featuring Prehistoric period archaeology. If you wish to see news reports for general European archaeology, please go to The Archaeology of Europe Weblog.

Wednesday, August 12, 2020

About 30 previously unknown stones discovered at Carahunge (the Armenian Stonehenge)

About 30 previously unknown stones with holes have been discovered at Carahunge or Zorats Karer (the Armenian Stonehenge).

Other stones of astronomical importance have also been found during the measurement works carried out jointly by the Byurakan Observatory and the Armenian National University of Architecture and Construction.

The team carried out computer scanning of the monument and the adjacent area, aerial photo-scanning of the area. All stones with holes were photographed and measured.

Read the rest of this article...

DES TOMBES GAULOISES AUX PORTES DE NÎMES (GARD)

À l'ouest du centre-ville de Nîmes, l'Inrap vient de mettre à jours des vestiges de l’âge du Fer à l’Antiquité ; sépultures, champs et voirie.

Sur prescription de la DRAC Occitanie, une fouille préventive menée par l’Inrap s’est déroulée de mai à août 2020, à l’ouest du centre-ville actuel de la ville de Nîmes, préalablement à la construction d’un immeuble d’habitation.

DES TOMBES GAULOISES

La découverte principale de cette opération est un ensemble funéraire en bon état de conservation dont l’emprise s’étend au-delà des limites de la fouille. Daté entre les VIe et Ve siècles avant notre ère, cet ensemble comprend trois sépultures à incinération, deux vases ossuaires en céramique grise monochrome et un dépôt de résidus en fosse. Le mobilier métallique associé, couteaux et fibules, indique qu’il s’agit pour deux d’entre elles de personnages appartenant à la sphère masculine.

Read the rest of this article...

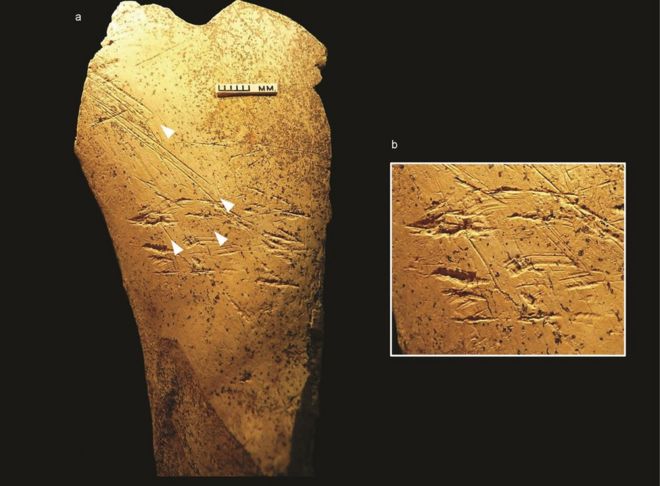

Europe's earliest bone tools found in Britain

One of the oldest organic tools in the world. A bone hammer used to make the fine flint bifaces from Boxgrove. The bone shows scraping marks used to prepare the bone as well as pitting left behind from its use in making flint tools

UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY

The implements come from the renowned Boxgrove site in West Sussex, which was excavated in the 1980s and 90s.

The bone tools came from a horse that humans butchered at the site for its meat.

Flakes of stone in piles around the animal suggest at least eight individuals were making large flint knives for the job.

Researchers also found evidence that other people were present nearby - perhaps younger or older members of a community - shedding light on the social structure of our ancient relatives.

Read the rest of this article...

Monday, August 10, 2020

"Woodhenge” discovered in prehistoric complex of Perdigões

Archaeological excavations in the Perdigões complex, in the Évora district, have identified "a unique structure in the Prehistory of the Iberian Peninsula", Era -Arqueologia announced.

Speaking to the Lusa agency, the archaeologist in charge, António Valera, said that it was "a monumental wooden construction, of which the foundations remain, with a circular plan and more than 20 metres in diameter".

It is "a ceremonial construction", a type of structure only known in Central Europe and the British Isles, according to the archaeologist, with the designations as 'Woodhenge', "wooden versions of Stonehenge", or 'Timber Circles' (wooden circles).

The structure now identified is located in the centre of the large complex of ditch enclosures in Perdigões and "articulates with the visibility of the megalithic landscape that extends between the site and the elevation of Monsaraz, located to the east, on the horizon".

Read the rest of this article...

Burnt remains from 586 BCE Jerusalem may hold key to protecting planet

A new analysis of 1st Temple-era artifacts, magnetized when Babylonians torched the city, provides a way to chart the geomagnetic field – physics’ Holy Grail – and maybe save Earth

The Bible and pure science converge in a new archaeomagnetism study of a large public structure that was razed to the ground on Tisha B’Av 586 BCE during the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem. The resulting data significantly boosts geophysicists’ ability to understand the “Holy Grail” of Earth sciences — Earth’s ever-changing magnetic field.

“The magnetic field is invisible, but it plays a critical role in the life of our planet. Without the geomagnetic field, nothing on Earth would be as it is — maybe life wouldn’t have evolved without it,” Hebrew University Prof. Ron Shaar, a co-author of the study, told The Times of Israel.

In the new study published in the PLOS One scientific journal, lead author and archaeologist Yoav Vaknin harvested data from pieces of floor from a large, two-story building excavated in the City of David’s Givati parking lot. Minerals embedded in the dozens of floor chunks were heated at a temperature higher than 932 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius) and magnetized during the slash and burning of ancient Jerusalem, and therefore offered up geomagnetic coordinates.

Read the rest of this article...

Detectorist 'shaking with happiness' after Bronze Age find

Items believed to be pieces of the Bronze Age harness were also found

CROWN COPYRIGHT

A metal detectorist was left "shaking with happiness" after discovering a hoard of Bronze Age artefacts in the Scottish Borders.

A complete horse harness and sword was uncovered by Mariusz Stepien at the site near Peebles in June.

Experts said the discovery was of "national significance".

The soil had preserved the leather and wood, allowing experts to trace the straps that connected the rings and buckles.

This allowed the experts to see for the first time how Bronze Age horse harnesses were assembled.

Mr Stepien was searching the field with friends when he found a bronze object buried half a metre underground.

He said: "I thought 'I've never seen anything like this before' and felt from the very beginning that this might be something spectacular and I've just discovered a big part of Scottish history.

Read the rest of this article...

Metal detectorist unearths ‘nationally significant’ Bronze Age hoard

Bronze Age harness

A metal detectorist has discovered a hoard of Bronze Age artefacts in the Scottish Borders which experts have described as “nationally significant”.

Mariusz Stepien, 44, was searching a field near Peebles with friends on June 21 when he found a bronze object buried half a metre underground.

The group camped in the field and built a shelter to protect the find from the elements while archaeologists spent 22 days investigating.

Among the items found were a complete horse harness – preserved by the soil – and a sword which have been dated as being from 1000 to 900 BC.

Mr Stepien said: “I thought I’ve never seen anything like this before and felt from the very beginning that this might be something spectacular and I’ve just discovered a big part of Scottish history.

Read the rest of this article...

Mystery ancestor mated with ancient humans. And its 'nested' DNA was just found.

An unidentified ancestor that interbred with humans may have been Homo erectus (skull shown here).

(Image: © Shutterstock)

The ancestor may have been Homo erectus, but no one knows for sure — the genome of that extinct species of human has never been sequenced, said Adam Siepel, a computational biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and one of the authors of a new paper examining the relationships of ancient human ancestors.

The new research, published today (Aug. 6) in the journal PLOS Genetics, also finds that ancient humans mated with Neanderthals between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago, well before the more recent, and better-known mixing of the two species occurred, after Homo sapiens migrated in large numbers out of Africa and into Europe 50,000 years ago. Thanks to this ancient mixing event, Neanderthals actually owe between 3% and 7% of their genomes to ancient Homo sapiens, the researchers reported.

Read the rest of this article...

Wednesday, August 5, 2020

Skeletons reveal wealth gap in Europe began to open 6600 years ago

Some early European farmers seem to have been much better off than others

Chelsea Budd/Umeå University

A wealth gap may have existed far earlier than we thought, providing insight into the lives of some of Europe’s earliest farmers.

Chelsea Budd at Umeå University in Sweden and her colleagues analysed the 6600-year-old grave sites of the Osłonki community in Poland, to try to determine whether wealth inequality existed in these ancient societies.

The team first found that a quarter of the population was buried with expensive copper beads, pendants and headbands. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that these people were richer during their lifetimes.

“The items could simply have been a performance by the surviving family members,” says Budd. “It could be used to mitigate the processes surrounding death or even to promote their own social status.”

Read the rest of this article...

Remains of 10,000-year-old woolly mammoth pulled from Siberian lake

A newly discovered woolly mammoth skeleton found on the Yamal peninsula in Siberia, Russia, is remarkably well preserved. Photograph: mvk.yanao/ Instagram

Rare find includes skin, tendon and excrement of what is thought to be an adult male

Russian scientists are poring over the uniquely well-preserved bones of a 10,000-year-old woolly mammoth after completing the operation to pull them from the bottom of a Siberian lake.

Experts spent five days scouring the silt of Lake Pechenelava-To in the remote Yamal peninsula for the remains, which include tendons, skin and even excrement, after they were spotted by local residents. About 90% of the animal has been retrieved during two expeditions.

Read the rest of this article...

Monday, August 3, 2020

Update on the Asclepeion dig at Epidaurus

Credit: Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports

Culture Minister Lina Mendoni on Thursday visited the archaeological site at the Epidaurus Asclepeion to be briefed on the progress of recent archaeological excavations which have revealed the remains of an even older temple building found at the shrine, in the vicinity of the Tholos.

The partially-excavated building, which is dated to about 600 B.C., consists of a ground floor with a primitive colonnade and an underground basement chipped out of the rock beneath. The stone walls of the basement are covered in a deep-red-colored plaster and the floor is an intact pebble mosaic, which is one of the best-preserved examples of this rare type of flooring to survive from this era.

The find is considered significant because it predates the impressive Tholos building in the same location, whose own basement served as the chthonic residence of Asclepius, and which replaced the newly-discovered structure after the 4th century B.C.

Read the rest of this article...

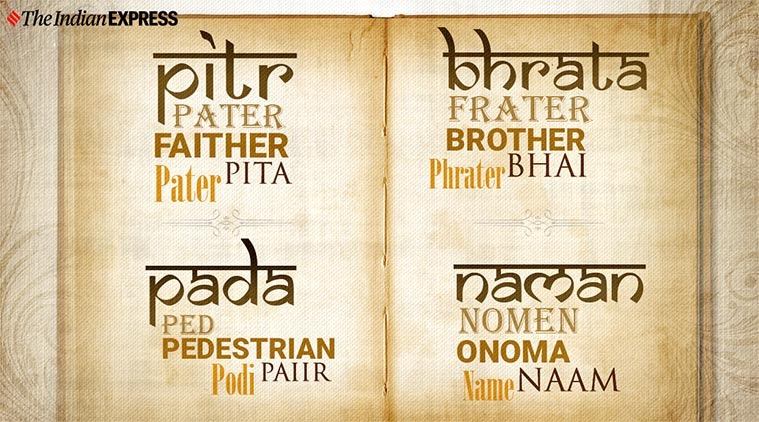

Why Sanskrit has strong links to European languages and what it learnt in India

Jones’ claim rested on the evidence of several Sanskrit words that had similarities with Greek and Latin. (Photo created by Gargi Singh)

Newer scholarship has shown that even though Sanskrit did indeed share a common ancestral homeland with European and Iranian languages, it had also borrowed quite a bit from pre-existing Indian languages in India.

In 1783, the colonial stage in Bengal saw the entrance of William Jones who was appointed judge of the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William. In the next couple of years, Jones established himself as an authority on ancient Indian language and culture, a field of study that was hitherto untouched. His obsession with the linguistic past of the subcontinent, led him to propose that there existed an intimate relationship between Sanskrit and languages spoken in Europe.

Jones’ claim rested on the evidence of several Sanskrit words that had similarities with Greek and Latin. For instance, the Sanskrit word for ‘three’, that is ‘trayas’, is similar to the Latin ‘tres’ and the Greek ‘treis’. Similarly, the Sanskrit for ‘snake’, is ‘sarpa’, which shares a phonetic link with ‘serpens’ in Latin. As he studied the languages further, it became clearer that apart from Greek and Latin, Sanskrit words could be found in most other European languages.

Read the rest of this article...

Sunday, August 2, 2020

Ancient bones in disturbed peat bogs are rotting away, alarming archaeologists

Peat moss around a pool in Cairngorms National Park in the United Kingdom

DUNCAN SHAW/SCIENCE SOURCE

The wrinkles on the face of “Tollund Man” are still visible, even though he died more than 2200 years ago. The mossy wetlands in Denmark that mummified his body are ideal for preserving organic matter, giving archaeologists an extraordinary window into our distant past. But a recent excavation at a similarly boggy site in Sweden shows these perfect conditions are fragile, and when they break down, so, too, do the bodies, bones, and other organic remains that have been preserved for centuries. The finding suggests a long-standing tenet of archaeology—avoiding excavation and leaving artifacts in the ground for long-term preservation—needs revisiting, at least for some wetland sites.

Anecdotal evidence has long suggested the condition of remains excavated from wetlands like peat bogs is declining, says Benjamin Gearey, a wetland archaeologist at University College Cork who was not involved with this study. For example, bone deterioration has been documented at Star Carr, an archaeological site in northern England. But it’s been hard to know how widespread the pattern is–and how fast the decay is occurring.

Ageröd, a peat bog in the south of Sweden that holds bones, antlers, and other artifacts from Mesolithic cultures that flourished more than 8000 years ago, is a good place to measure the pace of decay in a peat bog, says Adam Boethius, an archaeologist at Lund University. Boethius and his colleagues compared bones freshly excavated in 2019 with bones that had been exhumed from the bog in the 1940s and 1970s and stored in the Lund University Historical Museum. They rated the weathering of each bone, from well-preserved ones—those that were shiny and crack-free—to dull bones with worn outer surfaces.

Read the rest of this article...

Stonehenge: Sarsen stones origin mystery solved

The origin of the standing sarsens at Stonehenge had been impossible to identify until now

The origin of the giant sarsen stones at Stonehenge has finally been discovered with the help of a missing piece of the site which was returned after 60 years.

A test of the metre-long core was matched with a geochemical study of the standing megaliths.

Archaeologists pinpointed the source of the stones to an area 15 miles (25km) north of the site near Marlborough.

English Heritage's Susan Greaney said the discovery was "a real thrill".

The seven-metre tall sarsens, which weigh about 20 tonnes, form all fifteen stones of Stonehenge's central horseshoe, the uprights and lintels of the outer circle, as well as outlying stones.

Read the rest of this article...

Study Suggests Bones Preserved in Peat Bogs May Be at Risk

Bogs are perhaps best known for preserving prehistoric human remains. One of the most famous examples of these so-called "bog bodies" is Tollund Man. (Getty Images)

Per the paper, archaeologists need to act quickly to recover organic material trapped in the wetlands before specimens degrade

Peat bogs are notoriously uninhabitable. When low in oxygen, they don’t support microbial life, and without microbes, dead humans and animals caught in the spongy wetlands fail to decompose. Thanks to this unusual characteristic, peat bogs have long been the scene of incredible archaeological discoveries, including naturally mummified human remains known as bog bodies.

But new research published in the journal PLOS One presents evidence that bogs are losing their body-preserving abilities. As Cathleen O’Grady reports for Science magazine, archaeologists found that the best-preserved artifacts recovered from bogs in 2019 resemble the worst-preserved ones found in the 1970s, while the best-preserved specimens from the ’70s are on par with the worst retrieved in the 1940s. (Bogs’ lack of oxygen, as well as an abundance of weakly acidic tannins, preserves artifacts as delicate as small mammal and bird bones.)

The findings suggest that archaeologists may need to act quickly to uncover what’s left in the world’s bogs.

“If we do nothing, wait and hope for the best, it is likely that the archaeo-organic remains in many areas will be gone in a decade or two,” the authors say in a statement. “Once it is gone there is no going back, and what is lost will be lost forever.”

Northern Europe is dotted with peat bogs, which stood out among the thickly forested prehistoric landscape and may have served as spiritual places. “Half earth, half water and open to the heavens, they were borderlands to the beyond,” wrote Joshua Levine for Smithsonian magazine in 2017.

Many bog bodies show signs of horrific violence. Theories regarding these unlucky individuals’ deaths—and unusual mode of interment—range from execution to robberies gone wrong and accidents, but as archaeologist Miranda Aldhouse-Green told the Atlantic’s Jacob Mikanowski in 2016, the most likely explanation is that these men and women were victims of ritualized human sacrifice.

Read the rest of this article...

Neanderthal Genetics May Explain Your Low Tolerance for Pain

NURPHOTOGETTY IMAGES

Turns out your eldest ancestors sexual antics might be the reason you’re especially sensitive to painful stimuli.

If you have a low tolerance for pain new research suggests you should blame it on our Neanderthal cousins.

According to joint research from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany and Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet, “people who inherited a special ion channel from Neanderthals experience more pain.”

In their paper, the researchers describe Nav1.7, a sodium channel “crucial for impulse generation and conduction in peripheral pain pathways,” which showed reduced inactivation in Neanderthals. Researchers deduced that because of this lowered level of activation, Neanderthals experienced heightened pain sensitivity in comparison to modern humans.

Read the rest of this article...

Archaeology Take a tusk, drill holes, weave a rope – and change the course of history

he fragments found at Hohle Fels cave in Germany that scientists now recognise as a rope-making tool from 40,000 years ago. Photograph: University of Tübingen

Scientists have discovered the tool our stone-age ancestors used to manufacture twine – a milestone in technological development

Forty thousand years ago, a stone-age toolmaker carved a curious instrument from mammoth tusk. Twenty centimetres long, the ivory strip has four holes drilled in it, each lined with precisely cut spiral incisions.

The purpose of this strange device was unclear when it was discovered in Hohle Fels cave in south-western Germany several years ago. It could have been part of a musical instrument or a religious object, it was suggested. But now scientists have concluded that it is the earliest known instrument for making rope. And its impact would have been revolutionary.

Our stone-age ancestors would have been able to feed plant fibres through the instrument’s four holes and by twisting it create strong ropes and twines. The grooves round the holes would have helped keep the plant fibres in place.

Read the rest of this article...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

:focal(3042x1756:3043x1757)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/e7/8b/e78ba0c2-264f-4bba-97c8-2281d02fa3df/gettyimages-599000988.jpg)