Excavating the Smerquoy Hoose [Credit: © Colin Richards]

The study is part of a much wider project, The Times of Their Lives, funded by the European Research Council (2012-2017), which has applied the same methodology to a wider series of case studies across Neolithic Europe. That project has demonstrated many other examples of more dynamic and punctuated sequences than previously suspected in 'prehistory'.

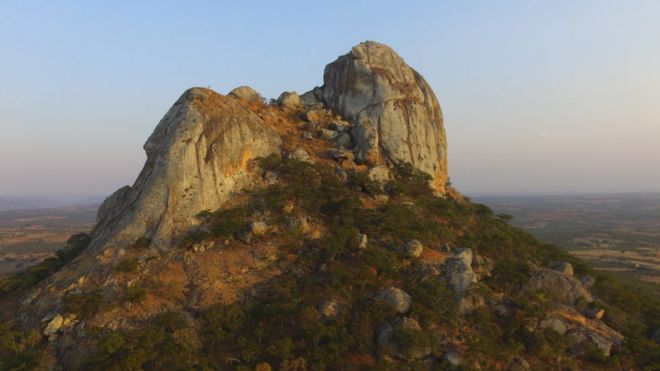

Neolithic Orkney is well-preserved and is a time of stone houses, stone circles and elaborate burial monuments. World-renowned sites such as the Skara Brae settlement, Maeshowe passage grave, and the Ring of Brodgar and Stones of Stenness circles have long been known and are in the World Heritage Site (given this status in 1999). They have been joined by more recent discoveries of great settlement complexes such as Barnhouse and Ness of Brodgar.

The new study reveals in much more detail than previously possible the fluctuating fortunes of the communities involved in these feats of construction and their social interaction. It used a Bayesian statistical approach to combine calibrated radiocarbon dates with knowledge of the archaeological contexts that the finds have come from to provide much more precise chronologies than those previously available.

Read the rest of this article...