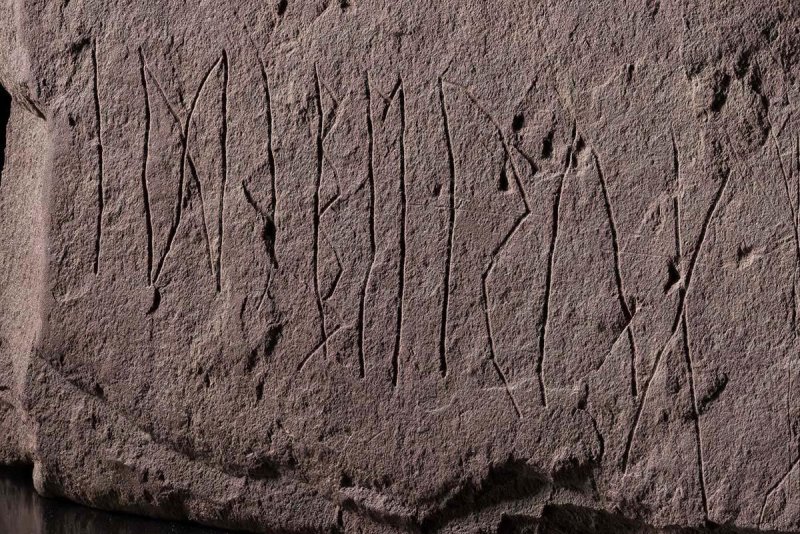

The Svingerud Stone is the oldest rune stone, created almost two thousand years ago

There are many things that come into mind when thinking of Vikings – horned helmets, which are historically inaccurate, longships that brought terror to Europe, Norse gods that have been turned into Hollywood super heroes and, the subject of this article, their unique way of writing.

The runic alphabet developed among the early Germanic people of Northern Europe almost 2,000 years ago. How it was created it still not fully understood, though it is widely believed that contact with Mediterranean civilisations – Greeks, Etruscans and Romans – influenced the creation of this writing system.

Some of the best preserved examples of this script can be found on rune stones, including the lions-hare located in Sweden. They had many varied purposes ranging from marking territory to memorialising fallen kinsmen. Rune stones used to be highly colourful, though hundreds of years of being out in the open means very little is left for modern observers.

Here were look at some of the oldest rune stones found by archeologists.

Read the rest of this article...