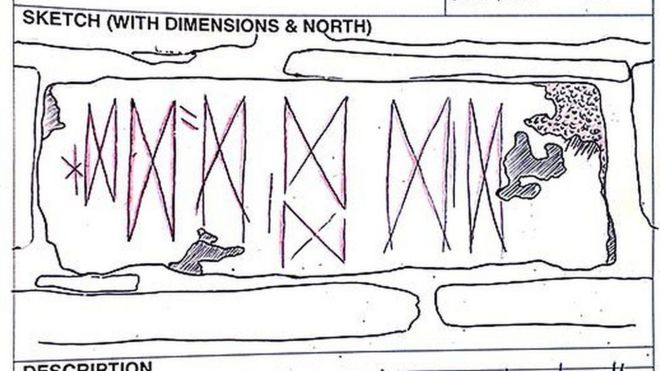

Archaeological remains of individual MC337 excavated from the site of Hipogeu de Monte Canelas I, Portugal, and analysed by the archaeologist Rui Parreira and the anthropologist Ana Maria Silva.

Credit: Rui Parreira

The genomes of individuals who lived on the Iberian Peninsula in the Bronze Age had minor genetic input from Steppe invaders, suggesting that these migrations played a smaller role in the genetic makeup and culture of Iberian people, compared to other parts of Europe. Daniel Bradley and Rui Martiniano of Trinity College Dublin, in Ireland, and Ana Maria Silva of University of Coimbra, Portugal, report these findings July 27, 2017 in PLOS Genetics.

Between the Middle Neolithic (4200-3500 BC) and the Middle Bronze Age (1740-1430 BC), Central and Northern Europe received a massive influx of people from the Steppe regions of Eastern Europe and Asia. Archaeological digs in Iberia have uncovered changes in culture and funeral rituals during this time, but no one had looked at the genetic impact of these migrations in this part of Europe. Researchers sequenced the genomes of 14 individuals who lived in Portugal during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages and compared them to other ancient and modern genomes. In contrast with other parts of Europe, they detected only subtle genetic changes between the Portuguese Neolithic and Bronze Age samples resulting from small-scale migration. However, these changes are more pronounced on the paternal lineage.