The idea of these early humans being plant-eating, self-medicating sophisticates has been brought into question by the findings of researchers at London's Natural History Museum.

The Prehistoric Archaeology Blog is concerned with news reports featuring Prehistoric period archaeology. If you wish to see news reports for general European archaeology, please go to The Archaeology of Europe Weblog.

Sunday, October 20, 2013

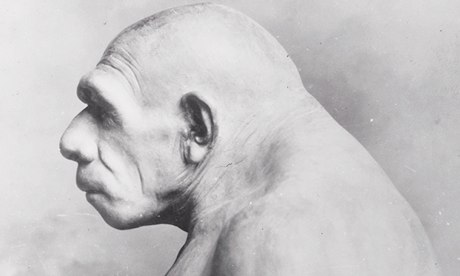

The stomach-turning truth about what the Neanderthals ate?

The idea of these early humans being plant-eating, self-medicating sophisticates has been brought into question by the findings of researchers at London's Natural History Museum.

Jersey's place in Neanderthal history revealed in study

Saturday, October 19, 2013

Neanderthals used toothpicks to alleviate gum disease

Removing food scraps trapped between the teeth one of the most common functions of using toothpicks, thus contributing to our oral hygiene. This habit is documented in the genus Homo, as early as Homo habilis, a species that lived between 1.9 and 1.6 million years ago.

New research based on the Cova Foradà Neanderthal fossil shows that this hominid also used toothpicks to mitigate pain caused by oral diseases such as inflammation of the gums (periodontal disease). It is the oldest documented case of palliative treatment of dental disease done with this tool.

This research is based on toothpicking marks on the Neanderthal teeth related to periodontal disease. The chronology of the fossil is not clear, but the fossil remains were associated with a Neanderthal Mousterian lithic industry (about 150,000 to 50,000 years).

Read the rest of this article...

Friday, October 18, 2013

5200 BC House Discovered in Romania

Recently , we shared with you some recent discoveries in Romania, from various periods. Apparently there is room for more, as the biggest house from the pre-Cucuteni period, 5200-5100 BC was just found in Baia, Suceava. Experts from the Cambridge University support this research, seeking to identify how the grain trade between China and Europe was made at that time.

Read the rest of this article...

Skull Find Could Change Picture of Early Human Evolutionary History

We may have to change some thinking about early human evolution in a major way, suggests researchers, after studying new fossil finds at the site of Dmanisi in the Republic of Georgia. What has previously been thought to be separate ancient human species - Homo erectus,Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, and Homo ergaster, for example, may actually be variations of one and the same species. This is the conclusion of a recent examination of fossil finds uncovered at this, the world's earliest known hominid site outside of Africa.

1.8M-year-old skull gives glimpse of our evolution, suggests early man was single species

Archaeologists rediscover the lost home of the last Neanderthals

Blow to multiple human species idea

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

Frogs' legs may have been English delicacy 8,000 years before France

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Bronze Age Europe – the first Industrial revolution

s part of a larger pan-European study investigating the Bronze Age of Europe, an archaeologist from the University of Gothenburg has provided the first evidence of long distance travel by an individual – probably from southern Sweden – into the territory of the Únětice culture of Silesia.

The doctoral thesis confirms evidence based on bioarchaeological data.

A traveller from Sweden

‘Over 3800 years ago, a young male, possibly born in Skåne, made a journey of over 900 kilometres south, to Wroclaw in Poland”. concludes Dalia Pokutta, author of the thesis. He met his end violently in Wroclaw, killed in the territory of the Úněticean farmers. His remains were discovered in association with two local females, who had been killed at the same time.Read the rest of this article...

Amesbury dig 'could explain' Stonehenge history

The site already boasts the biggest collection of flints and cooked animal bones in north-western Europe.

Read the rest of this article...

Iron Age camp unearthed at UK quarry

Archaeologists have unearthed an Iron Age enclosure while excavating land at the edge of a working quarry.

|

| Archaeologists are excavating land close to Potgate Quarry [Credit: Steve Timms/BBC] |

Dig leader Steve Timms said the site was later brought back into use in the early Roman period as a paddock.

Read the rest of this article...

Forscher enträtseln die Bevölkerungsentwicklung Europas in der Jungsteinzeit

Die bisher umfangreichste und detaillierteste genetische Studie zur Besiedlungsgeschichte Europas während des Neolithikums ergab deutliche Hinweise auf vier wesentliche Migrationsereignisse in der Zeit zwischen dem 6. und 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Für die heute in Science veröffentlichte Studie untersuchten Anthropologen aus Mainz und Adelaide in Kooperation mit Archäologen aus Halle (Saale) hunderte DNA-Proben von jungsteinzeitlichen Skelettfunden aus dem Mittelelbe-Saale-Gebiet.

Read the rest of this article...

Friday, October 11, 2013

European origins laid bare by DNA

DNA from ancient skeletons has revealed how a complex patchwork of prehistoric migrations fashioned the modern European gene pool.

The study appears to refute the picture of Europeans as a simple mixture of indigenous hunters and Near Eastern farmers who arrived 7,000 years ago.

The findings by an international team have beenpublished in Science journal.

DNA was analysed from 364 skeletons unearthed in Germany - an important crossroads for prehistoric cultures.

Read the rest of this article...

Link to Oetzi the Iceman found in living Austrians

Austrian scientists have found that 19 Tyrolean men alive today are related to Oetzi the Iceman, whose 5,300-year-old frozen body was found in the Alps.

Their relationship was established through DNA analysis by scientists from the Institute of Legal Medicine at Innsbruck Medical University.

The men have not been told about their connection to Oetzi. The DNA tests were taken from blood donors in Tyrol.

Read the rest of this article...

Monday, October 7, 2013

Shock Bronze Age find 'changes history'

The farm was discovered in the area between Backen and Klabböle in an area known as Klockaråkern and it is thought that the farm was in use for almost 600 years from around 1100 BC.

Read the rest of this article...