Pottery from the Verson archaeological site (France), analyzed in the research

[Credit: Annabelle Cocollos, Conseil Departemental du Calvados]

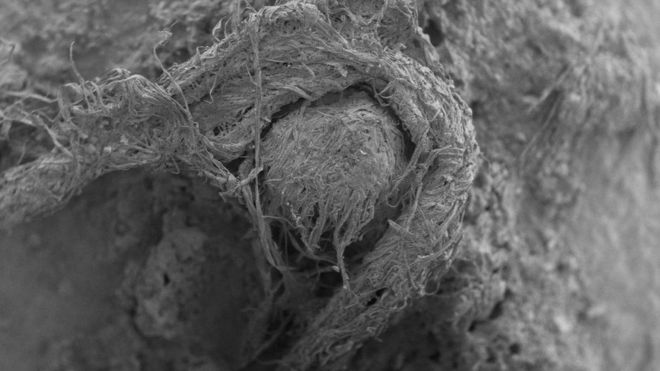

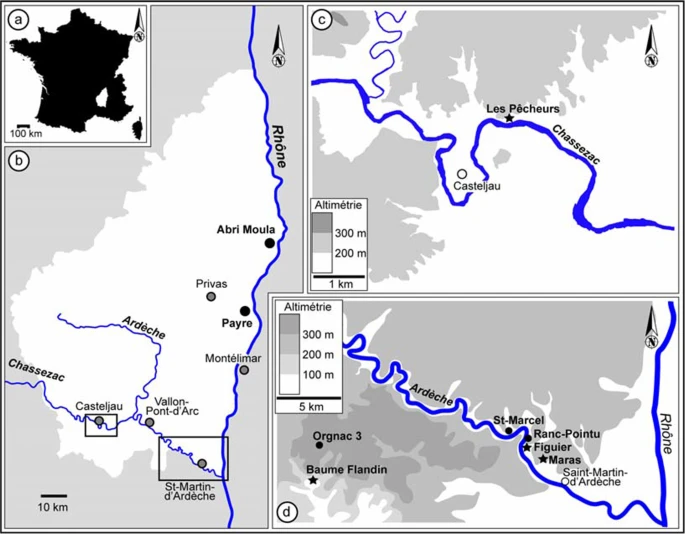

A study has tracked the shift from hunter-gatherer lifestyles to early farming that occurred in prehistoric Europe over a period of around 1,500 years. An international team of scientists, led by researchers at the University of York, analysed the molecular remains of food left in pottery used by the first farmers who settled along the Atlantic Coast of Europe from 7,000 to 6,000 years ago.

The researchers report evidence of dairy products in 80% of the pottery fragments from the Atlantic coast of what is now Britain and Ireland. In comparison, dairy farming on the Southern Atlantic coast of what is now Portugal and Spain seems to have been much less intensive, and with a greater use of sheep and goats rather than cows.

The study confirms that the earliest farmers to arrive on the Southern Atlantic coast exploited animals for their milk but suggests that dairying only really took off when it spread to northern latitudes, with progressively more dairy products processed in ceramic vessels.

Prehistoric farmers colonising Northern areas with harsher climates may have had a greater need for the nutritional benefits of milk, including vitamin D and fat, the authors of the study suggest.

Read the rest of this article...

/arc-anglerfish-syd-prod-nzme.s3.amazonaws.com/public/AG4XDMAKJ5FKXITHW4IJ7Q5WVY.jpg)