General view of the site with a circular enclosure from the Early Iron Age in the foreground

[Credit: Philippe Alix, Inrap]

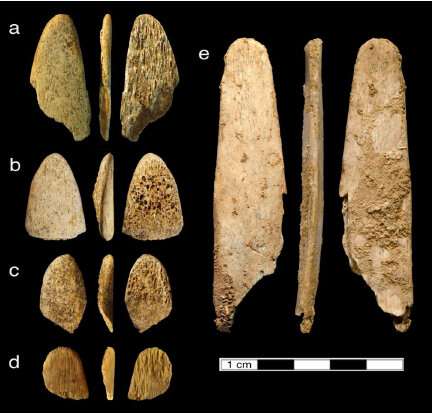

Several excavations have been requested by the DRAC Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes authorities since 2016 as part of the development of the Plaine de l'Ain Industrial Park (PIPA) in the commune of Saint-Vulbas. One of them, carried out by a team from Inrap, has, among other things, brought to light several funerary structures from the Early Iron Age.

The excavation of almost one hectare took place to the north of a vast protohistoric funerary area (Bronze Age and Iron Age), which was identified during the course of a series of preliminary surveys, extending over several dozens of hectares on the right bank of the Rhone.

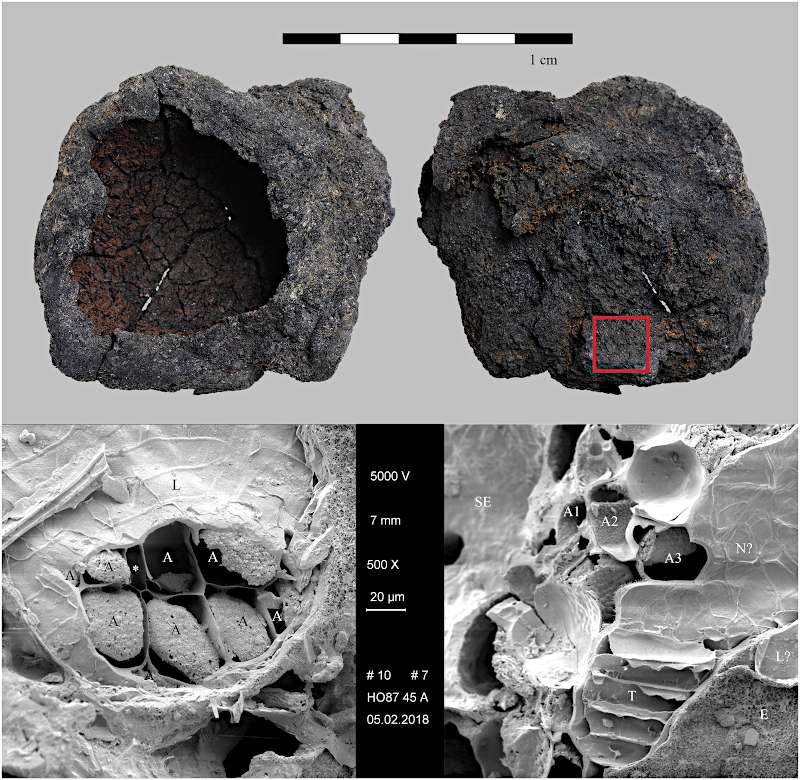

One burial and three circular enclosures, probably tumuli, were found from the very beginning of the Iron Age (first half of the 8th century BC), one of which still has a central cremation repository. Towards the end of the 5th century BC a new grave site was established which consists of cremation pit associated with a four-post aedicula in the centre of a small quadrangular enclosure.

Read the rest of this article...

_(9420310527).jpg/512px-Fl%C3%BBte_pal%C3%A9olithique_(mus%C3%A9e_national_de_Slov%C3%A9nie%2C_Ljubljana)_(9420310527).jpg?resize=512%2C768&ssl=1)